[dkpdf-columns columns=”3″ equal-columns=”false” gap=”10″]

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a major health problem worldwide with over 750,000 new cases per annum and nearly 300,000 deaths. In the United Kingdom, there are about 34,000 new cases per annum and 16,000 deaths equating to 50 people dying every day from the disease.The overall 5-year survival in the U.K, France and Germany is 45%, 50% and 60% respectively, correlating with earlier presentation of the disease in Germany. Furthermore, France and Germany have long-standing screening programmes for bowel cancer, unlike in the UK,which began its national bowel cancer screening programme just over 10 years ago.In Nigeria, the data is at best muddied and at worst, may be regarded as non-existent.However, published sporadic data indicate that the peak age of incidence of colorectal cancer is a mere 44 years compared to 67 years in Western Europe!

Nigerian patients are not only young but tend to have very aggressive disease characterised by bad prognostic histological features like poorly differentiated,spindle or mucinproducing cancer cells.Perhaps even more disheartening is the fact that more than 75% of patients in Nigeria present with advanced disease (stages 3 & 4)compared to just 30% of the screened population in Western Europe. The clinical outcome for patients in Nigeria who suffer from colorectal cancer will, therefore, remain abysmal without an urgent National strategy to tackle the disease.

Aetiology

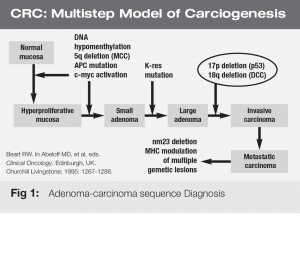

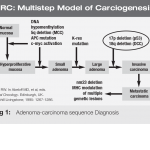

The exact cause of colorectal cancer is unknown, but it is now widely accepted that most bowel cancers arise from benign polyps or adenomas, that have undergone various genetic mutations possibly triggered by some yet undetermined environmental factor/s. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence (figure 1) is a model of colorectal carcinogenesis that was first described by Bert Vogelstein comprising of a series of mutations, deletions and suppression of cancer genes at the molecular level. Generally, colorectal cancer can be divided into two distinct groups.

A. Sporadic Cancers –The vast majority (about 90%) of colorectal cancer cases are sporadic. In these cases, the exact cause is unknown. However, anecdotal evidence appears to suggest that a complex interaction of a variety of environmental factors such as reduced fibre intake, excessive ingestion of red meat,carcinogens, obesity and smoking among others, contribute to the development of this type of colorectal cancer.

B. Hereditary Cancers –These contribute about 10% of all colorectal cancers and can be sub-divided into:

I. Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) – 8%.In this case, mismatch repair genes within the double-stranded DNA result in microsatellite instability and loss of apoptosis (programmed cell death) leading to the emergence of malignant cells. These genes can be detected in tumour tissue samples using specialised immuno- histochemical techniques and guide the clinician in recommending a screening strategy for offsprings or siblings of

patients with HNPCC.

II. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) – 2%.

These patients carry the FAP gene resulting in the formation of thousands of pre-malignant colonic polyps. Typically, these polyps are diagnosed when patients are in their teens, progressing to cancer in their early twenties and death before the age of 30.For this reason, these patients require surgery to remove the entire colon (total colectomy) once these polyps appear in an attempt to remove the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of colorectal cancer is based on a good history. Weight loss, rectal bleeding (any colour, frequency or quantity), change in bowel habit, tenesmus (feeling of incomplete emptying), anaemia, abdominal pain and/or

distension or palpable abdominal mass on physical examination.

Remember that a good clinical assessment includes a rectal examination (PR) and examination with a rigid or flexible sigmoidoscope and is completed by direct visualisation of the entire colon at colonoscopy (gold standard) or indirectly with barium studies (obsolete in developed countries).

One must ensure that colonoscopy is performed by a suitably qualified gastroenterologist or gastrointestinal surgeon who is trained to intubate the caecum (confirmation of a complete examination) and to recognise both normal and abnormal findings.

CT pneumocolon / virtual colonoscopy is a modern alternative where the risk of colonoscopy is unacceptably high or cannot be tolerated by the frail patient. Histological confirmation of cancer from tumour sample is required before staging investigation with a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, MRI for rectal cancer and an endo-anal ultrasound to define early rectal cancer that may be amenable to local excision.

Treatment

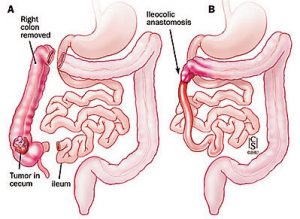

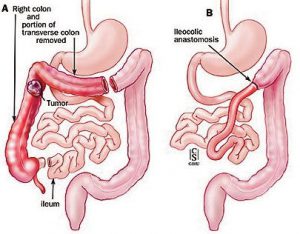

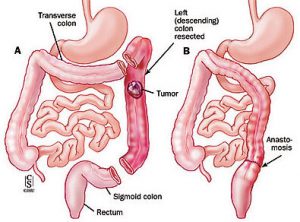

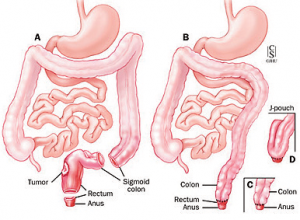

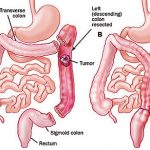

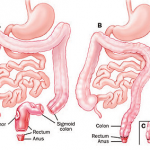

SurgerySurgery offers most people a realistic chance of disease cure – 80% of patients survive five years following curative resection (stage 1&2) and histological findings indicate that no further treatment is necessary. Surgical options for early colon cancer include a right, extended or left hemicolectomy with primary anastomosis for lesions in the right, transverse or left colon respectively (figure 2-4).

A high anterior resection is performed for rectosigmoid tumours while total mesorectal excision (TME) usually

with a temporary loop ileostomy is the gold standard operation for rectal tumours. In very low rectal cancers, a

sphincter-saving operation (colo-pouch anal anastomosis, figure 5) may be attempted provided a distal clearance margin of at least two centimetres is achieved. However,oncological clearance of a tumour should always take precedence over any attempt to save the sphincters in which case an abdominoperineal excision of the rectum with formation of a permanent colostomy must be undertaken. All excised specimens are staged histologically (Duke’s

and TNM classification) as the results confirm curative surgical resection or the need to recommend further adjuvant or palliative treatment.

Adjuvant Treatment for Colorectal Cancer

1. Surgery alone has failed to significantly improve overall survival from the disease.

2. Micrometastasis of cancer cells is thought to be the reason for failure of surgery alone.

3. A better understanding of tumour cell cycle indicates that micrometastases are susceptible to destruction by

chemotherapy agents.

Adjuvant treatment is usually in the form of chemotherapy, radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy has significant 3-5-year survival benefits in patients with nodepositive disease. The main cytotoxic agents are 5-Fluorouracil with Folinic acid, Oxaliplatin and Irinotecan in various combinations administered as an infusion over 306 months. The recent addition of immunotherapy agents such as cetuximab, panitumumab or bevacizumab confers additional survival benefits in this cohort of patients.

CPD UPDATE

- There are 750,000 new cases of colorectal cancer per annum worldwide and nearly 300,000 deaths

- Peak age of incidence of colorectal cancer in Nigeria is approximately 44 years (compared to 67 years in Western Europe)

- 75% of patients in Nigeria present with advanced disease (stages 3 & 4) compared to just 30% of the

screened population in Western Europe - The exact cause of bowel cancer is unknown but most arise from benign polyps or adenomas that have undergone genetic mutation triggered by environmental factors

- 90% of colorectal cancers are ‘sporadic’ or of unknown cause.

- FAP polyps typically progress to cancer in the early twenties and cause death before age 30

- Patients with FAP require surgery to remove the whole colon once these polyps appear

- Treatment modalities for colorectal cancer include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy depending on the type, site and stage of disease

- Screening for colorectal cancer prevents disease progression and improves prognosis

Radiotherapy

Adjuvant radiotherapy has no benefit in colon cancer. It is given in rectal cancer to reduce the rate of local recurrence or possibly ‘downstage’ the disease (down-sizing to increase the chances of successful surgical clearance). It may be given pre or post-operatively, either as a short (5 days) or long (4-6weeks) course

treatment. There is good evidence from randomised trials that short-course preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer significantly reduces local recurrence and improves survival, but toxicity attributed to therapy has reduced its popularity. Long course pre-operative radiotherapy is advocated for patients with locally advanced rectal cancers for the purpose of ‘downstaging’ the disease.Long course post-operative radiotherapy where there are bad prognostic indicators for local recurrence (lymphovascular invasion, poorly differentiated tumours and positive

circumferential margins) following curative resection with the proviso that patient did NOT receive pre-operative radiotherapy.

Combination therapy in the form of chemo-radiation is based on the concept that cytotoxic agents sensitise tumour cells to downstaging by radiation. This form of neo-adjuvant therapy (given pre-operatively) is expected

to increase in popularity particularly with the development of newer more effective chemotherapy agents.

Liver Resection

Hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastasis is associated with a five-year survival of about 30%.Generally, less than four metastases confined to one lobe of the liver may be amenable to surgical resection, but this indication has been extended in the hands of experienced liver surgeons. However, the timing of surgery remains controversial,

whether hepatectomy should be synchronous with resection of the bowel primary or, perhaps delayed for three months prior to re-staging of the disease. In Europe, most surgeons favour a delayed approach, as this permits selection of patients with rapidly progressive disease who are unlikely to benefit from surgery.

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)

Radiofrequency energy has emerged as a useful modality to ablate in-situ liver metastases where the lesions are considered irresectable or in selected cases, in combination with liver resection. This form of treatment is

administered percutaneously under general anaesthesia and radiological control by expert radiologists in highly specialised units. Current evidence indicates that RFA alone does not provide survival benefit comparable to liver

resection.

Palliative Care

Patients with disseminated colorectal cancer,irresectable primary tumours unresponsive to chemoradiation are referred to the palliative care team. Symptom relief with a variety of drugs is the primary goal of palliation.

Infrequently, surgery is indicated in the form of a debulking or bypass procedure.

Screening

Screening for colorectal cancer offers the opportunity to prevent the disease developing or to improve prognosis by treating the premalignant (polyps) and early stage disease.There is good evidence from randomised trials that screening for colorectal cancer with faecal occult blood testing saves lives and amounts to a 15-18% reduction in cumulative mortality.Furthermore, 43% survival benefit was shown in the screened population of a randomised trial

using flexible sigmoidoscopy. However,colonoscopy remains the gold standard and should be undertaken by qualified

gastroenterologist / gastrointestinal surgeon trained to complete the examination (caecal intubation with photographic evidence) and to recognise normal from abnormal findings. An incomplete examination is potentially

catastrophic for the patient, so it is important to interrogate the operator regarding their experience, how many procedures they have performed previously and their complication rates. It is not customary in Nigeria to question

a so-called “expert”. However, in view of the high stakes involved, I would advise that the clinician that calmly (and satisfactorily)addresses your concerns without resorting to irritation, anger or self-justification ought indeedto be the doctor of choice.

[/dkpdf-columns]

read moreDisclosure forms provided by the author are available at NEJM.org.

Editor’s note:

Author Affiliations

Supplementary Material

| Disclosure Forms | 83KB |

Add your Comment

Add your Comment

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BHQJ 2018 ; 001:34-36

Related Article

Medical Negligence & the Law5th May 2018 . Atrogenic harm is a matter of significant concern in Nigeria admin

Colorectal Cancer Overview5th May 2018 . [dkpdf-columns columns="3" equal-columns="false" gap="10"] Introduction Colorectal cancer is a major admin

Funding Healthcare Services in Nigeria – A conundrum of demand, policy and supply!5th May 2018 . [dkpdf-columns columns="3" equal-columns="false" gap="10"] Doctor, I happy say na you admin

5 “Provocations” of Healthcare Quality Reform6th May 2018 . [dkpdf-columns columns="3" equal-columns="false" gap="10"] n the four decades since he admin

Health Insurance, Activism & Urgent Change6th May 2018 . [dkpdf-columns columns="3" equal-columns="false" gap="10"] AR: Dr Soyinka, it’s wonderful to admin

Anne Olowu talks about her “Masterclass” experience6th May 2018 . [dkpdf-columns columns="3" equal-columns="false" gap="10"] As I suspect is the case admin

Stomach & Oesophageal Cancer in Nigeria6th May 2018 . [dkpdf-columns columns="3" equal-columns="false" gap="10"] Gastric and Oesophageal (Upper GI) cancers admin

Setting out the Stall!7th May 2018 . [dkpdf-columns columns="3" equal-columns="false" gap="10"] "The drawbacks of our false knowledge admin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.